Does prostate cancer make stress worse? For many men dealing with prostate cancer, the answer is a definite yes; of course it does. Having prostate cancer is worrisome – even today, when there is more hope of successful treatment than ever before. But it’s not just the cancer itself. It’s the hassle of wrangling with an insurance company, and the worry about medical bills or taking time off for treatment; it’s frustration over a slower-than-expected recovery of urinary continence or sexual potency. It’s anxiety about the next PSA test. It’s unanswered questions and uncertainty, and worry that life will never get back to normal. Yes, there’s stress, and plenty of it.

But here’s a question that may be even more significant:

Does stress make prostate cancer worse? This one’s not so easy to answer. “Everybody has an individual response to stress,” says medical oncologist Suzanne Conzen, M.D., Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF)-funded investigator and Chief of Hematology and Oncology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. And that’s the key, she adds: it’s not so much the stress itself but the physiological response that can take a toll, and that may hinder our ability to fight cancer.

The body responds to stress with a surge of corticosteroids; primarily cortisol. When our ancient ancestors were running for their lives from a savage beast, it was this stress hormone, cortisol – along with adrenaline – that kicked in and saved their bacon. “We are hard-wired to respond to stress with this ‘fight or flight’ response.” Unfortunately, many of us react to everyday troubles with the same surge of stress hormone as if we were facing a sabertooth tiger – as if we were under attack. Our hypothalamus, located in the most primitive part of the brain, tells our adrenal glands, “This is the big one! Go to Defcon 3.” And cortisol, revving up in its effort to save us – a chemical version of someone running around in a panic, shouting, “Ohmygod, ohmygod,” can cause harm instead, affecting normal functions including the immune system, and even changing genes that are expressed in cancer cells.

“Some people have a higher stress response than others. It could be an inherited tendency; or they haven’t necessarily developed effective ways of coping with exposure to stressors,” says Conzen. “However, not all people who have a high stress response get cancer; and a lot of people are under stress and don’t get cancer. But that’s the complexity: not everybody who smokes gets lung cancer, but smoking is a risk factor. What you want to do is reduce your risk factors,” and your response to stress – like a bad diet, or smoking, or being overweight – is a risk factor for prostate cancer that can be changed.

“We think high cortisol levels are probably not a good thing in men who have prostate cancer. At least a subset of those men may have tumors that respond to high levels of stress because the prostate cancer expresses a protein, the glucocorticoid receptor, that is activated by cortisol,” says Conzen. And although Conzen is working on how to determine who these men are, right now, there’s no way to know for sure.

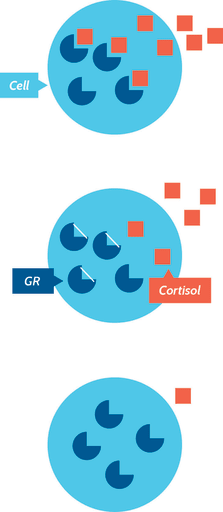

Cortisol, a hormone, attaches to a protein called the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in cells throughout your body, and this is like flipping a switch that activates stress in all those cells, including cancer cells. In ovarian cancer, Conzen has shown, higher levels of these receptors in the tumor tissue are linked to more aggressive, even lethal, disease. And in prostate cancer, she has found that the GR “is more highly expressed in cancer that is resistant to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).”

But it’s complicated, she adds: “We think it’s not only how much GR your tumor has, it’s how active it is.” With a PCF Challenge Award, Conzen and colleagues in her lab are working to find a way to measure how active cortisol and GR are in a prostate tumor, “whether it’s turning on and off a lot of genes, or just a few genes. The amount of GR does not necessarily correlate with the activity of the protein.”

So, how to fix it – if a man has aggressive prostate cancer, and high cortisol/GR activity? “One hypothesis would be, deprive that tumor of your body’s stress hormone receptor activity, by keeping the stress hormones relatively low.” This could happen with some type of medication – or, it could happen with stress reduction. What is that, exactly? It could mean making changes in your life, so there are fewer stressful factors in it. It also could mean making changes in you – with the help of such things as exercise, yoga, meditation, and counseling.

Note: Conzen does not believe that stress, all by itself, causes prostate cancer. “My guess is that GR-mediated stress signaling in the tumor cells probably has more to do with promoting aggressiveness and progression of cancer,” and perhaps recurrence of cancer. When Conzen talks about stress, she doesn’t mean a single traumatic incident, such as a car crash: “The kind of stress we’re talking about is daily unremitting stress.” Those countless little things that add up, day after day.

Also with PCF funding, Conzen and colleagues are working to identify which genes in prostate cancer cells are involved with the stress response, and what those genes are doing when the tumor cell GR is activated in a man who already has prostate cancer. “If we knew that, we would know when it would be useful to give a drug [a GR-modulator] to block it,” especially if they could find a drug that would only work in prostate cancer cells [see graphic]. Glucocorticoid receptors are expressed in a subset (~20%) of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Indeed, Dr. Conzen and colleagues have initiated clinical trials testing such GR-modulators in breast cancer, prostate cancer, and other cancer types. In advanced prostate cancer, there are at least three ongoing clinical trials testing GR-modulators: 1) enzalutamide alone vs. with the GR-modulator mifepristone; 2) the GR-modulator CORT125134 plus enzalutamide; and 3) the GR-modulator CORT125181 plus enzalutamide.

In the meantime, stress reduction may help achieve similar results, by lowering circulating cortisol activity in prostate cancer patients. Clinical trials are needed, Conzen notes, to show the effectiveness of stress response-reducing measures including cognitive behavioral therapy, medication, yoga, and mindfulness in prostate cancer patients. Such trials have been done in breast cancer, she says, “and have shown that there is a beneficial effect.”

Conzen also is also interested in understanding whether daily, continuous stressors could play a role in the aggressiveness of prostate cancer affecting African American men. “Prostate cancer tends to be more lethal in African American men, and, to date, environmental factors have not been identified. Social stressors and the stress response should be considered in trials designed to understand this disparity.”

The good news is that for general health, there are several concrete steps people can take to help deal with stress more effectively. Try just 1-2 of these for a month and note how your body – and mind – respond. Download PCF’s wellness guide, The Science of Living Well, Beyond Cancer, for more tips.

- Spend time in person with friends. Research suggests that in-person socializing (vs. through social media) is important: limited face-to-face contact may double your risk of depression, but making the effort to have in-person conversations creates a more fulfilling experience. Take time to meet a friend in person for coffee, or start a monthly activity group with friends who share the same interests.

- Give yoga a try. Despite what you might have seen on sitcom TV, yoga practice isn’t about twisting yourself into a pretzel; the goal is to connect your body and mind in a way that gives you peace, power, and clarity. Research continues to find links between yoga and decreased anxiety and depression, and better regulation of your hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system, which controls cortisol secretion. Check to see if your gym offers classes, take a free trial class at your local studio, or look for online classes through your computer.

- Get a pet. Research suggests that pet ownership alleviates stress-related blood pressure increases, and especially helps reverse depressive symptoms in the elderly. Dogs in particular are great stress-reducing companions, but consider volunteering at an animal shelter or visiting a dog park if you can’t own one yourself.

- This is an oldie but a goodie: working up a sweat can release endorphins, help your self-confidence, and improve mood-related disorders.

- Get your sleep right. With jobs, commitments, and Candy Crush, it’s easy to find yourself still awake at 4:00 a.m. with work the next day. But your body needs time to rest and recover: lack of sleep can increase your cortisol levels and may negatively impact your immune system.